The Watchmaker Argument

Hi friendly readers. I know a lot of you may have many different beliefs and philosophies on life. Now this is all well and good, but regardless of what beliefs you may hold, please, for the benefit of everyone, do not use the following argument.

You may have heard this argument before, as it comes in many forms. It is often called the watchmaker argument, or the watchmaker analogy. It has been described in many different ways by many people, but the basic idea is this:

|

Walking through a forest, you discover a watch lying on the ground. Due to its complex nature, you assume it is designed by some intelligence. Thus, by this reasoning, since life is even more complex, it must have also been designed by some intelligence."

|

This statement does have an element of truth to it. If you did not know what a watch was, and you were walking through a forest, and discovered one, you would probably correctly determine that it was designed by some intelligence. This argument however, has many other problems, which I will soon discuss.

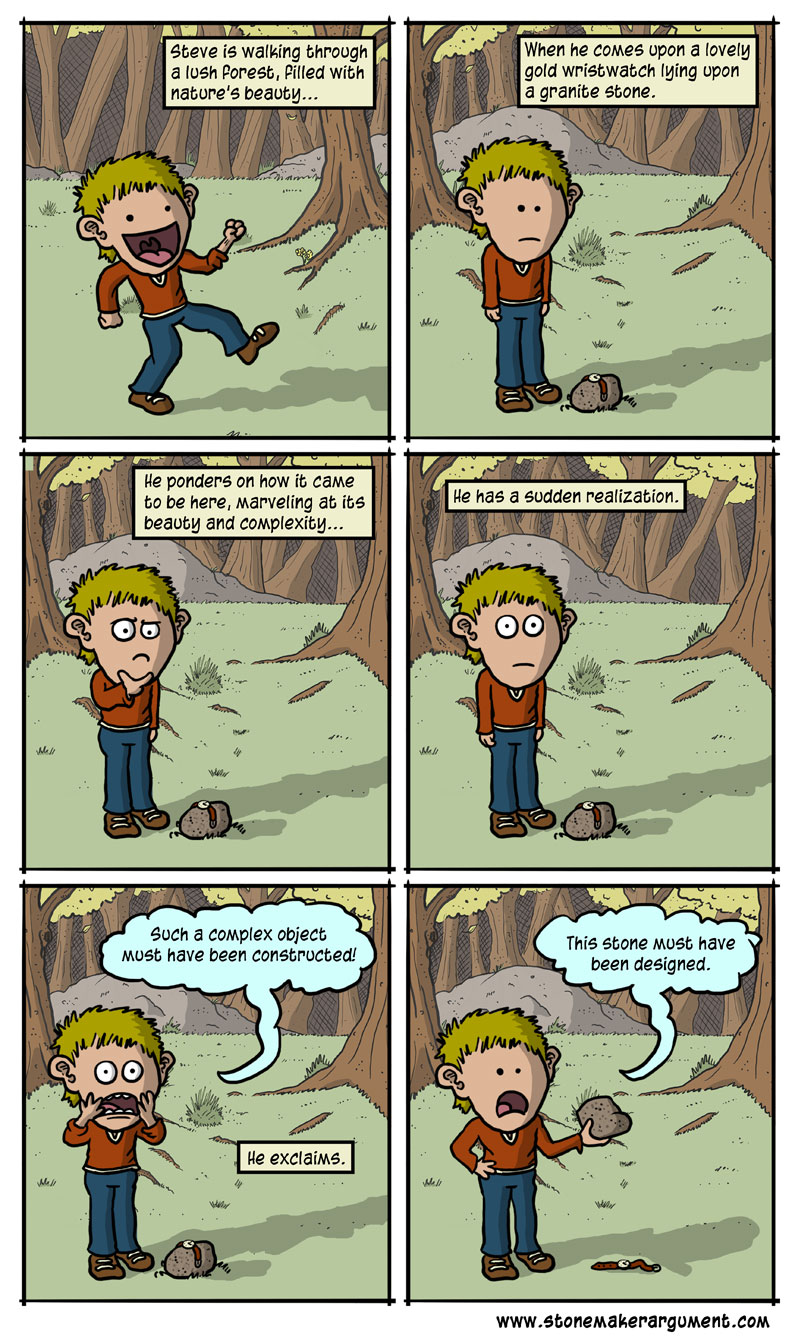

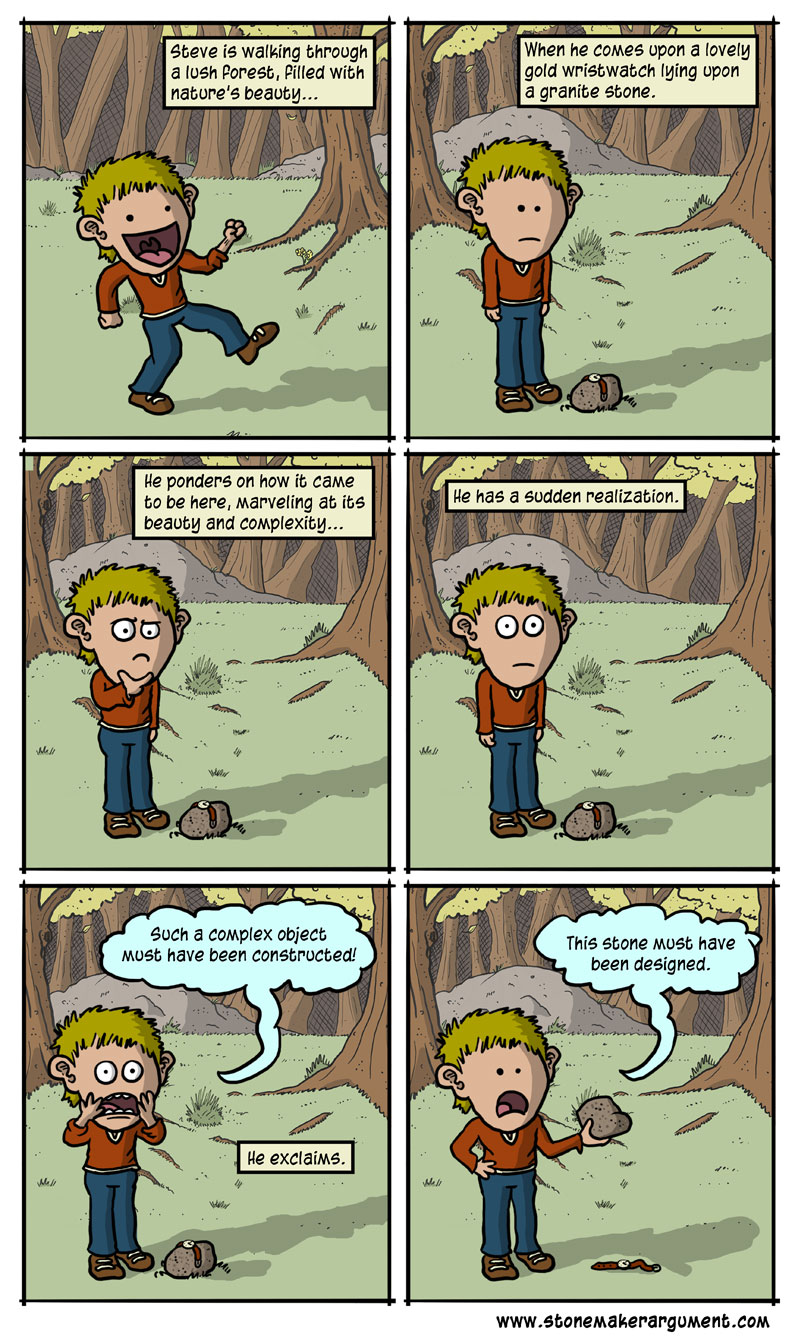

But first, l'd like to introduce you to Steve. Steve is a professional hypothetical man, who conveniently has never seen a watch in his life. Let's put our hypothetical friend in our hypothetical forest, and see what he discovers...

|

Steve has mistakenly raised a good point. Trees, animals, even rocks all have varying levels of complexity. So by the argument's own admission, shouldn't the watch blend in with the "designed" forest around it? If we singled out the watch, wouldn't that mean that the watch is somehow more designed than the rest of the forest?

Yet we likely would single out a watch in a forest. So what leads us to single out the watch? Perhaps the answer is not complexity, but something far simpler.

Life occurs in nature. It is self sustaining, has a mechanism for change and reproduction. Watches, on the other hand, do not occur in nature, and do not have a mechanism for change or reproduction. Watches for example, have not roamed the earth for millions of years reproducing and slowly changing over time.

|

Thank you Steve.

Let's examine a more current use of this argument.

"Look at this camera. It must be designed because of how complex it is. Now look at the human eye. Like the camera, it is also complex. Thus, the human eye must have been designed."

Firstly, one should note that regardless of whether or not the conclusion is true or false, the analogy itself is a logical fallacy. Let's take a look:

1. A camera is complex, thus it is designed.

2. The human eye is complex, thus it is designed.

|

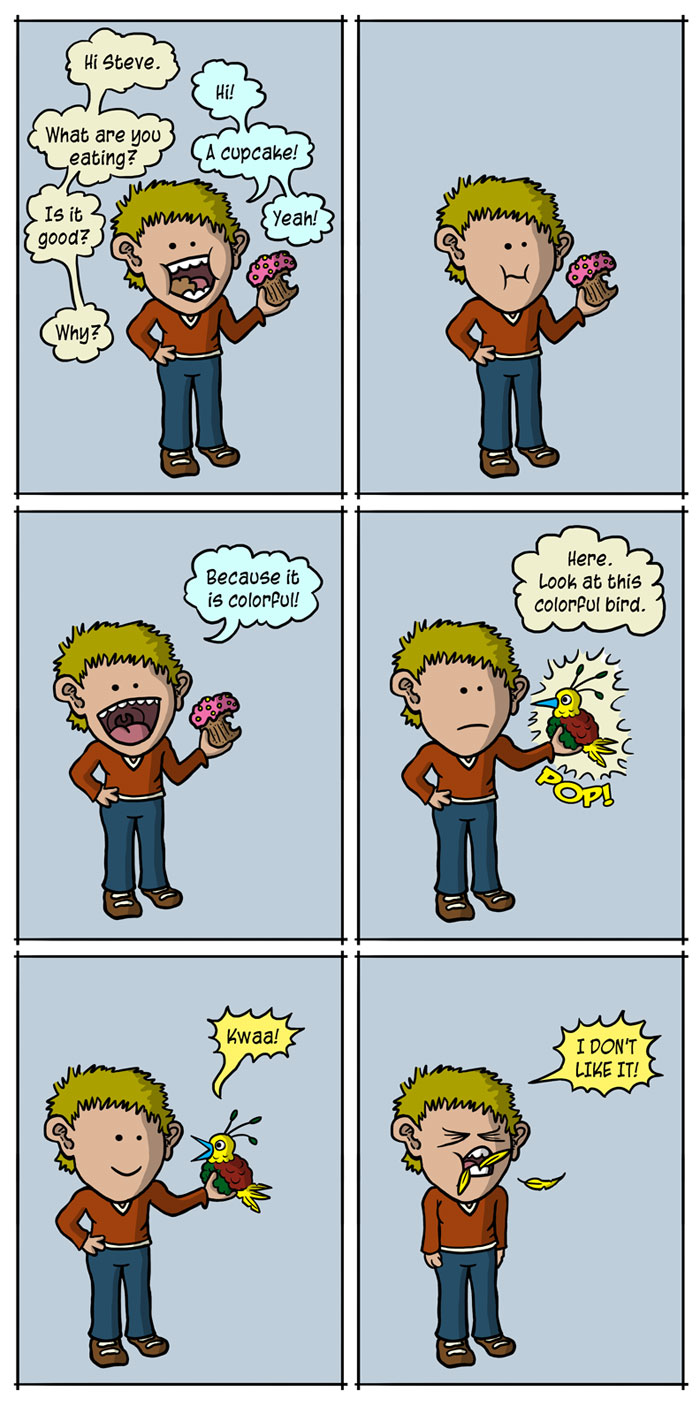

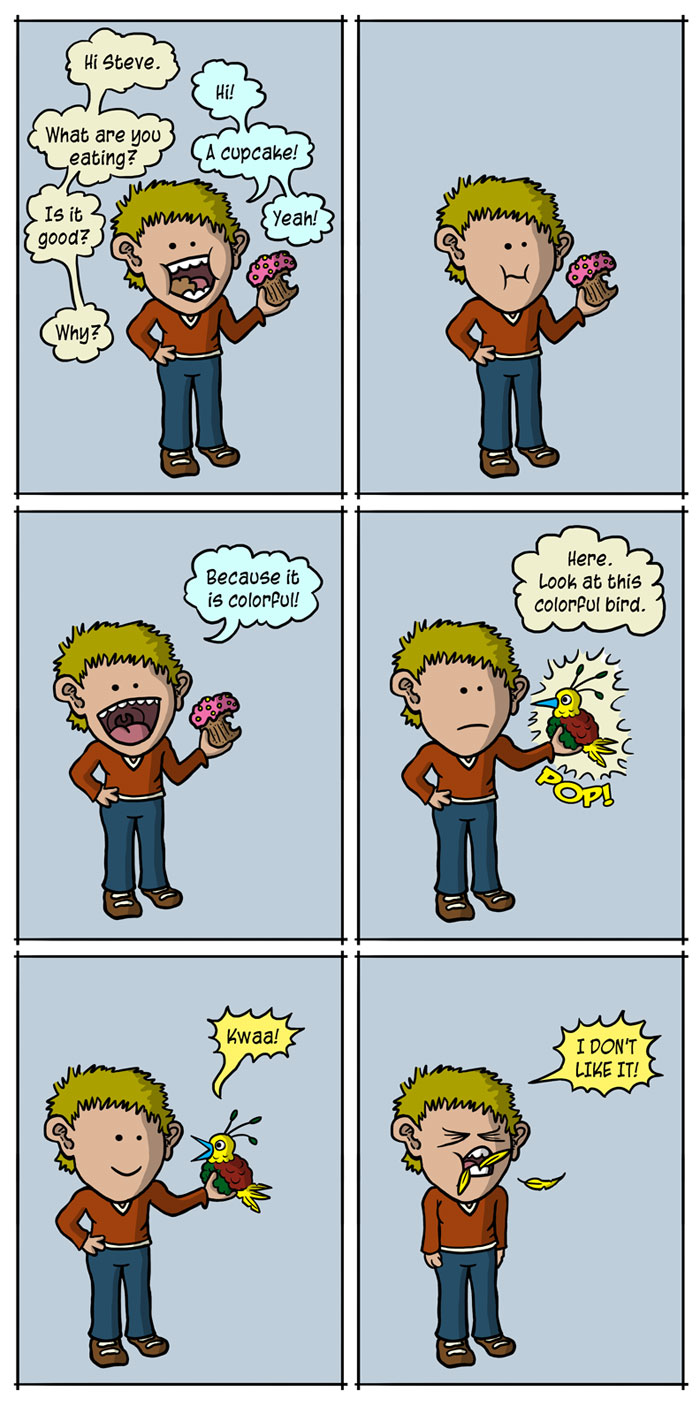

This is a non sequitur. Steve makes those all the time, let's ask Steve.

|

Thank you Steve, this is a perfect example:

1. A cupcake is colorful, thus it is delicious.

2. A bird of paradise is colorful, thus it too is delicious.

|

In both of these analogies, we first describe some true feature of an object (a camera is designed; a cupcake is delicious). We then try to come up with an explanation for this feature (the camera's complexity; the cupcake's color). In both cases the explanation is not proven, yet we apply it to a different object anyway (the eye, also complex, is designed; a bird of paradise, also colorful, is delicious).

This brings us to the true nature of this argument. Namely, if something is complex, it must be designed. But is complexity really what makes an object designed?

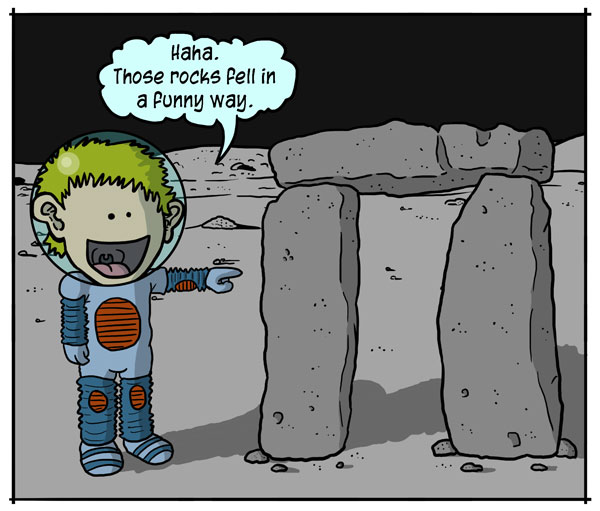

|

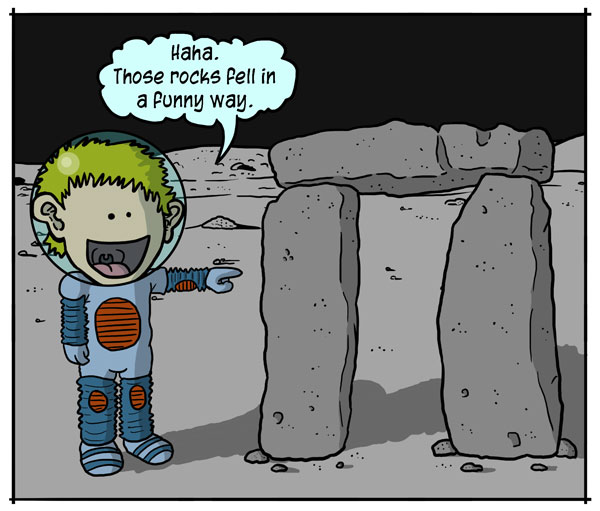

Steve's assertion, however crude, is probably correct. That bizarre rock formation is most likely designed. Would you call that rock formation complex? Not especially. Then what is it about this rock formation that makes it appear designed? Very simply, it is because rocks with that shape, and that arrangement do not occur naturally, and we have no natural mechanism to explain their arrangement other than chance. Essentially, either someone put those rocks there, or they happened to fall that way.

Since the idea of someone placing those rocks in that formation is more plausible than chance, it's reasonable to assume design in this case. However, if these rocks were found on the moon...

|

Exactly!

Finally, let us for the sake of argument, accept that the premise is true: Anything that is complex, must be designed. Wouldn't we then by our own premise, have to accept that the designer itself, which is complex by definition, must also be designed?

|

|

It seems that the watchmaker argument, in the end, is self-defeating.

|

|

|